I See You: Lessons in Human Dignity

This is a story that starts in Detroit, the part of the world I called home for 16 years before moving abroad. In many ways, Detroit and Dakar aren’t so different: rampant poverty, streets lined with abandoned and dilapidated buildings, great music.

This is a story about seeing. And feeling. And being human.

This is a story that starts with an old woman, a face mapped with wrinkles, the thin line of her toothless mouth opening and closing in a constant sucking motion.

For a few weeks, we’ve been making lunches and collecting supplies — toothbrushes, socks, tampons and whatnot — and bringing them to an area of the city where a large crowd of homeless people are living in an abandoned building with boarded up windows and rats the size of small dogs.

This isn’t a big organized group thing where a bunch of suburbanites show up with matching t-shirts and hand sanitizer in their pockets. Just a few families asking, “Hey, what can we do to make someone’s day better today?” Just our kids spending their Sunday afternoon making ham and cheese sandwiches for someone else.

As we hand out the sandwiches and ask people if they need anything else we have, the old woman approaches; slowly, stiffly, her head wobbly. Beneath a grey wool hat, she’s shaved her head, most likely to keep up with the lice. Her eyes have the look of rocks under water, glassy and worn. She reeks of alcohol.

She’s dragging a trash bag full of instant ramen noodles, food she’s picked up at a soup kitchen somewhere, food that will sustain her for at least a month. Mealworms and rats, she tells us, have gotten into everything else she tries to keep in the corner of the building where she sleeps.

I think about how insignificant our sack lunches are.

She pokes her head into the open rear of our car to see what kind of things she might be able to collect. While she’s stuffing a pair of socks into her garbage bag full of noodles, she stares at my friend, Jeff, who has been doing this a bit longer than we have. “I ‘member you,” she slurs. “You ‘member me?”

Jeff smiles. “Of course I remember you,” he says. “Diane, right?”

There’s this moment of suspended silence, a moment where the noisy world of the city pauses to whisper, I see you.

And then something unexpected happens.

Diane begins to cry.

The eyes that already looked underwater spill over. Tears trace the wrinkles down her cheeks. She doesn’t wipe them away.

I don’t know Diane — none of us do. I don’t know why she’s out on the streets. I don’t know if she has a family, or a friend. She’s the kind of person that most people would hurry past on the street, avoiding eye contact. Invisible.

But in that moment, Diane is somebody.

She has a name. She is known and recognized and seen. She is human.

It’s a moment that sears itself into my brain, and will replay itself over and over when I move to Dakar a year later.

Because while in Detroit I could return to my North-of-Eight-Mile (suburban) neighborhood, stop at the store to pick up something for dinner, and go back to being comfortably numb to the need and poverty and injustice a few miles away — in Dakar there’s no escape. It’s everywhere.

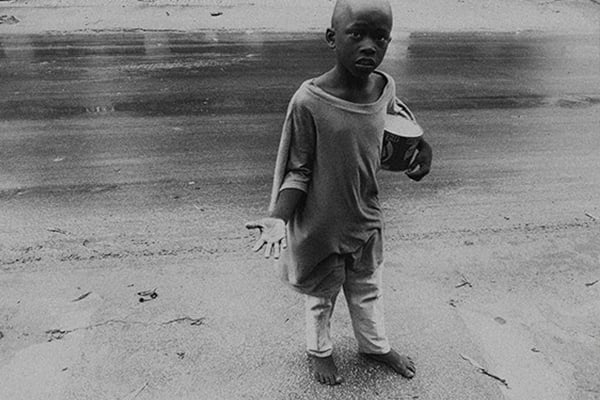

It’s the mother at the grocery store with a baby tied to her back who can’t afford to buy milk. It’s the talibé — young boys forced to beg all day on the streets and bring money back to their “teachers” — with their ragged clothes and bare feet on every corner, begging for money or bread or sugar. It’s the many mentally disabled people, including the guy who walks the streets completely naked, trying to survive in a world that has no resources to help them.

But in the midst of this poverty, I have also seen incredible displays of human dignity. I have watched a talibé take some leftover pizza I gave him back to the rest of the boys and divide it equally among them. I have watched an old woman hobbling to catch a car rapide (Dakar's version of a bus) that had just started to pull away from the curb, when two young men hanging out the back door stop the bus, jump off, and lift the tiny, frail woman up. I watched another young man stand up and give her his seat.

When a water pipe burst and the entire city was without running water for almost two months, the government sent water tankers into neighborhoods to fill people’s buckets. I watched as the flow of water dwindled to a trickle, with dozens of people and empty buckets still in line, half expecting a riot to break out. Instead, I watched people who had already received water moving along the line, pouring some of what they had into the buckets of those who had none.

While Diane in Detroit showed me how important it is to treat others with human kindness, Dakar has shown me how to do it. It’s humbling for a privileged white girl to realize that people with so little know so much more about what it means to treat others with dignity.

I’ve started asking the talibé who inevitably appear around my car when I go somewhere what their names are.

I shake a hand. “Nottu du?” I ask, in Wolof. They glance at one another, sharing silent looks of surprise. Finally, one boy says, “Mamadou.” And then there is giggling and laughing as all the boys shout their names — “Amet! Abdou! Malick!” — and jostle each other to shake my hand.

I may (or may not) give them money, but I hope I have given them something else — acknowledgement that they are more than their empty tomato cans.

.png)